..

CHAPTER 3: FUNGAL STRUCTURE AND ULTRASTRUCTURE

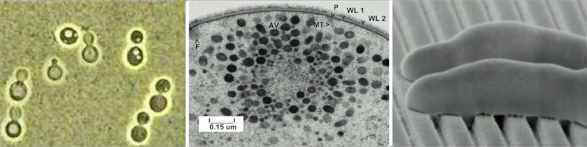

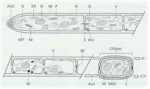

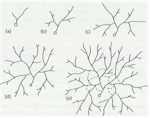

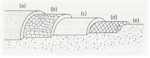

SAMPLE TEXT: Fungi have many unique features in terms of their structure, cellular components and cellular organisation. These features are intimately linked to the mechanisms of fungal growth and therefore to the many activities of fungi as decomposer organisms, plant pathogens and pathogens of humans. In this chapter we consider the main structural and ultrastructural features of fungi, and some of the powerful techniques that enable us to view the dynamics of subcellular components in living fungal hyphae, giving an insight into the way that fungi grow. OVERVIEW: THE STRUCTURE OF A FUNGAL HYPHA The hypha is essentially a tube with a rigid wall, containing a moving slug of protoplasm. It is of indeterminate length but often has a fairly constant diameter, ranging from 2 Ám to 30Ám or more (usually 5-10 Ám), depending on the species and growth conditions. Hyphae grow only at their tips, where there is a tapered region termed the extension zone; this can be up to 30Ám long in the fastest-growing hyphae such as Neurospora crassa which can extend at up to 40 Ám per minute. Behind the growing tip, the hypha ages progressively and in the oldest regions it may break down by autolysis or be broken down by the enzymes of other organisms (heterolysis). While the tip is growing, the protoplasm moves continuously from the older regions of the hypha towards the tip. So, a fungal hypha continuously extends at one end and continuously ages at the other end, drawing the protoplasm forward as it grows. The hyphae of most fungi have cross walls (septa; singular septum) at fairly regular intervals, but septa are absent from hyphae of most Oomycota and Zygomycota, except where they occur as complete walls to isolate old or reproductive regions. Nevertheless, the functional distinction between septate and aseptate fungi is not as great as might be thought, because septa have pores through which the cytoplasm and even the nuclei can migrate. Strictly speaking, therefore, septate hyphae do not consist of cells but of interconnected compartments, like the compartments of a train. This enables cellular components to move either forwards or backwards along dedicated pathways, so that a hypha can function as an integrated unit. All fungal hyphae are surrounded by a wall of complex organisation. It is thin at the apex (about 50 nm in Neurospora crassa) but thickens to about 125 nm at 250 nm behind the tip.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||