..

MORE IMAGES FROM CHAPTER 2

Fig. 2.35. Characteristic features of Oomycota. (a) Stages in the infection cycle of Phytophthora infestans (potato blight). Strains of opposite mating types in the host tissues produce antheridia and oogonia. Fertilisation leads to the production of thick-walled resting spores (oospores). After a dormant period, the oospores germinate by a hyphal outgrowth, which produces lemon-shaped, wind-dispersed sporangia. These initiate infection either by germinating as a hyphal outgrowth (in warm conditions) or by cytoplasmic cleavage to release motile biflagellate zoospores in cool, moist conditions. Infected leaves produce sporangiophores through the stomatal openings, leading to spread of infection to other plants. (b) Sexual reproduction by Saprolegnia; several oospores are formed in each oogonium. (c) Asexual reproduction in Saprolegnia: the sporangium develops at the tip of a hypha, then the protoplasm cleaves to release several primary zoospores (each with two anterior flagella). These encyst rapidly and the cysts release secondary zoospores (laterally biflagellate) for dispersal to new sites. (d) Asexual reproduction in Pythium. At maturity the sporangium discharges its contents into a thin, membraneous vesicle. The laterally biflagellate zoospores are cleaved within this vesicle which then breaks down to release the zoospores. [© Jim Deacon]

Fig.

2.37. Myxomycota. Top left: a plasmodium of Physarum

polycephalum growing on an agar plate. Note how the

plasmodium, which was inoculated in the centre of the

plate, has migrated towards the margin, where the

protoplasm has amassed. Top centre: a decaying

bracket fungal fruitbody (about 15 cm diameter)

completely covered by cream-coloured sporing structures

of the myxomycete Fuligo septica. Top right:

Mature sporangia of the slime mould Physarum cinereum

on a grass blade about 4 mm diameter; many of the

sporangia have opened to release the dark grey spores. Bottom

left: immature, pink sporangia of Lycogala on

the surface of rotting wood; each sporangium is about 1

cm diameter. Bottom right: similar sporangia 5

days later, when the sporangia had matured, turned grey

and consist of a thin papery sac that ruptures to release

the spores.

Fig. 2.38. Plasmodiophorids. Top left: Clubroot symptoms caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae on a cruciferous seedling: note the grossly deformed root system. Top right: large numbers of thick-walled resting spores of P. brassicae in clubroot tissue [Both images courtesy of J. P. Braselton, Ohio University; see http://oak.cats.ohiou.edu/~braselto/plasmos/]. Bottom

left and right: Clusters of thick-walled resting

spores of Polymyxa graminis at different

magnifications in the roots of grasses. [© Jim

Deacon]

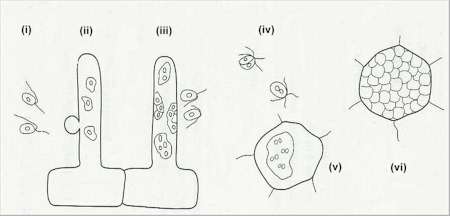

Fig. 2.39. Stages in the life cycle of Plasmodiophora brassicae, which causes clubroot disease of cruciferous crops. (i) Uninucleate primary zoospores are released from germinating resting spores in soil; (ii) the zoospores encyst on a root hair or root epidermal cell and inject a protoplast into the host cell; (iii) the protoplasts grow into small primary plasmodia and then convert to sporangia, which release zoospores into the soil when the root cell dies, or when an exit tube is formed; (iv) the zoospores fuse in pairs; (v) the fused zoospores infect root cortical cells and develop into secondary plasmodia; (vi) at maturity the secondary plasmodia covert into resting spores which often completely fill the cortical cells. These spores are finally released into soil when the roots decay. Eventually, the resting spores germinate to release haploid zoospores which repeat the infection cycle. [© Jim Deacon]

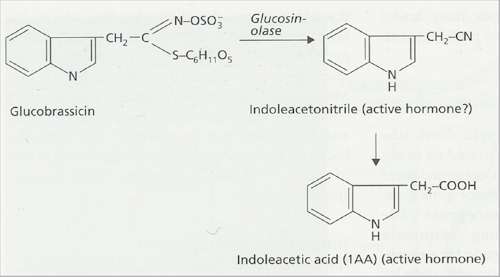

Fig. 2.40. Proposed conversion of glucobrassicin to the plant hormone indoleacetic acid by Plasmodiophora brassicae. [© Jim Deacon] |

|||||||||||