..

MORE IMAGES FROM CHAPTER

12: Fig. 12.13. Left: A method for detecting Pythium oligandrum or other mycoparasites in soil. Three soil crumbs (white arrowheads) were placed on an agar plate previously colonised by a soil fungus, Phialophora. Within 4 days, P. oligandrum started to grow across the Phialophora colony, collapsing the aerial hyphae (black arrowheads) and producing spiny-walled oogonia (top right). Bottom right: Narrow hyphae of P. oligandrum attacking and destroying a Phialophora hypha, leading to production of a spiny-walled oogonium. [© Jim Deacon]

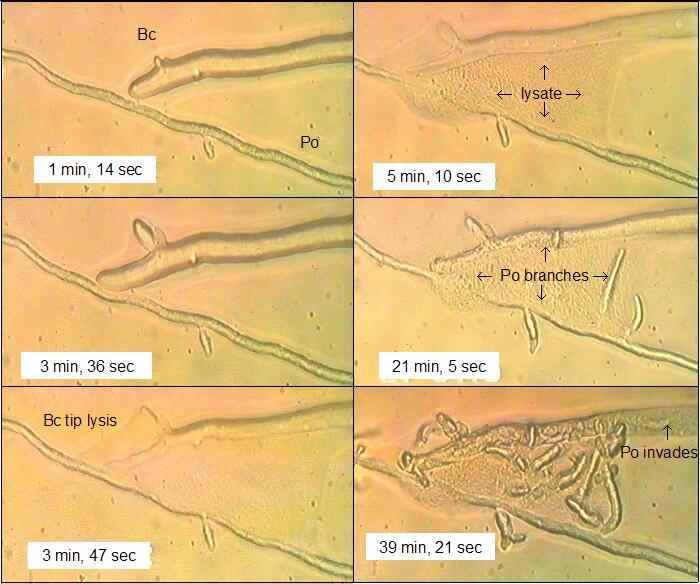

Fig. 12.14. Frames from a videotaped sequence when a hypha of Botrytis cinerea (Bc) contacted a hypha of Pythium oligandrum (Po) on a film of water agar. The times shown are from the start of recording (0 min). [© Jim Deacon]

Fig. 12.15. Frame from a videotaped sequence when Pythium oligandrum (growing from top right) contacted a hypha of Rhizoctonia solani. The Pythium hypha grew on, but within 5 minutes it branched at the contact point and coiled round the Rhizoctonia hypha. At about 49 min after the initial contact, P. oligandrum penetrated the host hypha and caused the protoplasm to coagulate.[© Jim Deacon]

Fig. 12.16. Take-all patch disease of turf on a golf-course green, caused by G. graminis var avenae. Note the poor quality of the turf, where the fine turf grasses have been killed by the fungus and have been replaced by weeds and course-leaved grasses. [© Jim Deacon] Fig. 12.17. The neck of a perithecium of G. graminis var avenae, with long (c. 80 µm) ascospores that are released from the apical ostiole and can infect turf grasses that are not protected by natural antagonists. [© Jim Deacon] Fig. 12.18. Colonisation of cereal or grass roots by Phialophora graminicola, a non-pathogenic parasite of roots that can effectively suppress invasion by the aggressive take-all fungus. From left to right: (1) dark runner hyphae of Phialophora in a grass root cortex; (2) clusters of darkly pigmented cells of Phialophora within the root cortex; (3) heavy invasion of the cortex of a cereal root by Phialophora, but the vascular tissues are not invaded; (4) at higher magnification, Phialophora hyphae have colonised the root cortex, but the endodermis (e) prevents invasion of the vascular tissues. [© Jim Deacon]

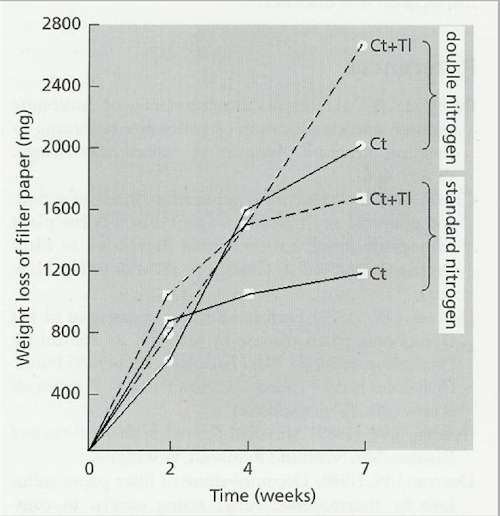

Fig. 12.19. Weight losses of filter paper (originally 7 g dry weight) in flasks inoculated with Chaetomium thermophile alone (Ct) or C. thermophile with the non-cellulolytic fungus Thermomyces lanuginosus (Ct+Tl) and incubated at 45oC. Mineral nutrients were supplied in the flasks with either a standard amount on nitrogen (C:N ratio 174:1) or double nitrogen (C:N ratio 88:1) [© Jim Deacon] |

|||||||||||