..

MAJOR TREE PATHOGENS: HETEROBASIDION ANNOSUM Heterobasidion annosum (Basidiomycota) is considered to be the most important cause of root rot of conifers in the Northern Hemisphere. It causes the disease commonly termed "Fomes root rot" (Because Heterobasidion annosum used to be called Fomes annosus) or "Annosus root rot". Heterobasidion is, essentially, a wound pathogen because the individual basidiospores are too small and too low in nutrients to penetrate the bark layer of the major woody roots of trees. However, during the felling of trees for timber extraction, or when a plantation is thinned to create the desired final tree density, the exposed stump surfaces provide an ideal environment for airborne basidiospores to germinate and initiate an infection focus. Once established in the stump tissues, the fungus grows down into the major roots and spreads from tree to tree by root grafts and root-to-root contact. Within a few years this leads to a progressively expanding focus of infection within a forest stand, and aerial surveys clearly identify these infection foci (Fig. 1). When the disease has reached this stage it will spread progressively below ground from tree to tree and eventually destroy the forest. The following images (Figs 2 and 3) show different stages in this process.

Fig 1. Aerial view of a young pine plantation in the Thetford region of Norfolk, England. Two large, spreading disease gaps are shown by arrowheads near the top of the image. [Image provided by courtesy of the late John Rishbeth; University of Cambridge]

Fig 2. A view of the forest canopy within a disease gap caused by H. annosum. Several of the trees have died, while others are growing poorly and will not be commercially viable. [Image provided by courtesy of the late John Rishbeth; University of Cambridge]

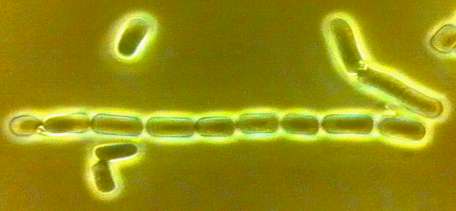

Fig. 3. As the trees die, H. annosum grows up to the soil surface and produces bracket-shaped fruitbodies just above or within the forest litter layer. The fruiting bodies release basidiospores that can be wind-dispersed and infect freshly exposed stump surfaces to spread the infection. [Image provided by courtesy of the late John Rishbeth; University of Cambridge] Potential solutions to this problem During many years of research, John Rishbeth developed a potential solution to this disease problem, based on a pioneering biological control system. He observed that freshly exposed stump surfaces were sometimes colonised naturally by a weakly parasitic fungus, now called Phlebiopsis gigantea. If the basidiospores of this fungus are applied to freshly cut stump surfaces these spores will germinate and colonise the stump surface, preventing Heterobasidion from invading the stump tissues. This became standard practice in pine plantations - both in North America and in Europe - and it proved to be remarkably successful. Phlebiopsis is only a weak parasite that naturally colonises dying stump tissues but does not pose a threat to healthy trees. In developing this disease-control system, Rishbeth made use of the fact that Phlebiopsis is one of the very few that can grow in an asexual (conidial) form in laboratory culture. Its hyphae readily fragment into brick-shaped spores in submerged liquid culture (Fig. 4). These spores can be stored for up to 6 months in a refrigerator if they are suspended in a sucrose solution at an osmotic potential that prevents them from germinating. The final stage in developing this biological control system was to produce suspensions that contained a harmless dye (bromocresol purple), so that the spore suspensions could be diluted (to allow the spores to germinate) and the dye would ensure that forestry workers could see that fresh stump surfaces had been treated with the biocontrol agent (Figs 5, 6, 7).

Fig 4. Spores of Phlebiopsis gigantea produced in liquid culture. [© Jim Deacon]

Fig 5. A tree stump (left) treated with a spore suspension containing spores of P. gigantea and bromocresol purple. There is probably some "artistic licence" in this image; it is unlikely that a diluted spore suspension would give such an intense colour! [Image provided by courtesy of the late John Rishbeth; University of Cambridge]

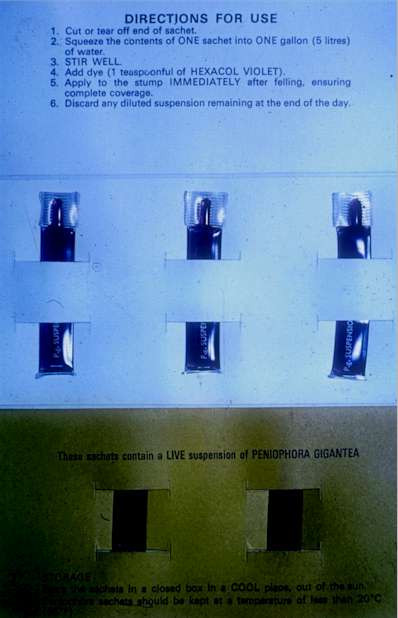

Fig 6. One of several commercial forms in which P. gigantea (formerly named Peniophora gigantea, as shown on the label) was used for stump protection. [© Jim Deacon]

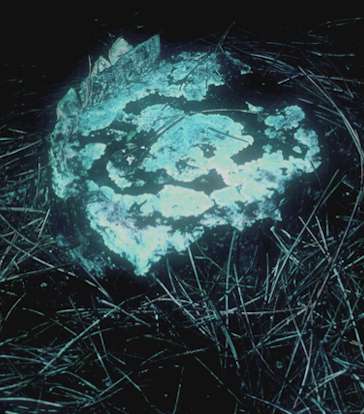

Fig 7. The surface of a cut pine stump one year after treatment with P. gigantea. The fungus has thoroughly colonised the stump tissues, preventing invasion by the pathogen, H. annosum. Phlebiopsis is a resupinate fungus - it grows as a thin crust on woody surfaces. Recent developments It would be nice to end the story here, with the development of one of the most important biological control systems available for any plant disease. But in the late 1990s it was discovered that Phlebiopsis spore suspensions, despite being used successfully for more than 30 years, had not been formally registered for use as commercial control agents - a procedure that is costly and does not (apparently) warrant the cost of registering the product. So it has been withdrawn from the US market, and there are now very few treatments that can be used against Heterobasidion. One of the limitations of P. gigantea had always been that it was effective only for protection of pine stumps and not for protection of spruce stumps. This is a significant limitation because Sitka spruce has, for some time, been the most commonly planted forestry tree in Britain. But in the last few years it has been recognised that the original strain of P. gigantea (used in most if not all biocontrol formulations) was selected from British pine plantations, whereas the strains of P. gigantea in Scandinavia are effective in protecting both pine and spruce stumps. It seems that the biocontrol strains of P. gigantea used in Britain are endemic strains, specialised to colonise pine stumps, whereas the strains used in Scandinavia have a broader host range and can protect spruce as well as pines. In Finland a commercial preparation of P. gigantea, marketed as Rotstop™, effectively controls H. annosum on spruce. The UK Forestry Commission is currently investigating the possibility of introducing such strains into Britain. Further discussion of these topics can be found in Chapter 10 of "Fungal Biology" |