..

CHAPTER 15: FUNGAL PARASITES OF INSECTS AND NEMATODES

Fig. 15.1. Spore-bearing structures of some common insect-pathogenic fungi. (a) Beauveria bassiana, which produces cream-white conidia alternately on an extending tip of a conidiophore. (b) Metarhizium anisopliae, which produces green conidia in chains from phialides. (c) Lecanicillium lecanii, which produces clusters of conidia in moisture drops at the tips of phialides. (d) Entomophthora spp (Zygomycota), which produce single terminal sporangia that are released at maturity and function as spores. [© Jim Deacon]

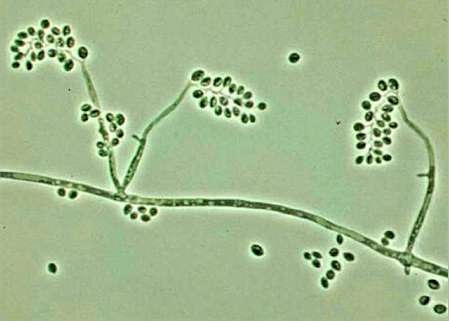

Fig. 15.2a. Spore-bearing structures of Beauveria bassiana in laboratory culture. The conidia typically develop in zigzag-like chains on long conidiophores. [© Image courtesy of G. L. Barron, with permission]

Fig. 15.2b An adult cicada beetle densely covered with white sporulating pustules of B. bassiana that have emerged through the intersegmental plates of the insect cuticle. [© Image courtesy of G. L. Barron, with permission]

Fig. 15.2c. Sporulation of Beauveria from between the cuticular plates of a naturally infected green cockchafer beetle [Image courtesy of Shirley Kerr; http://www.kaimaibush.co.nz/]

Fig. 15.2d Heavy infection of an adult pecan weevil by Beauveria. [© Image reproduced by courtesy of Louis Tedders (photographer) and USDA, Agricultural Research Service]

Fig. 15.2e: Grubs of pecan weevil at different stages of infection by Beauveria; healthy grubs are shown at left. [© Image reproduced by courtesy of Louis Tedders (photographer) and USDA, Agricultural Research Service]

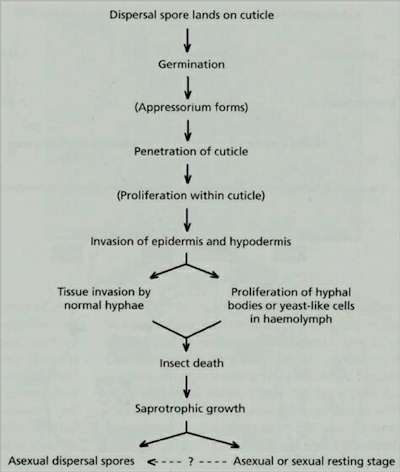

Fig. 15.3. General infection sequence of an insect-pathogenic fungus, based on Charnley (1989).

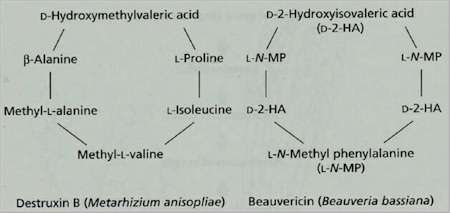

Fig. 15.4. Destruxin B and beauvericin, two cyclic peptides produced by insect-pathogenic fungi.

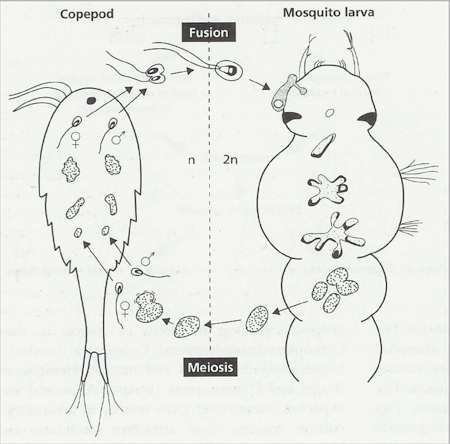

Fig. 15.5. Proposed life cycle of Coelomomyces psorophorae, which has an obligate alternation of generations. Diploid phase in a mosquito larva: a motile zygote attaches to the larva, encysts, produces an appressorium, then penetrates the host and produces a weakly branched mycelium. This gives rise to thick-walled resting spores that are released when the mosquito host dies. Haploid phase in a copepod (Cyclops vernalis): meiosis occurs in the resting sporangia and haploid zoospores of different mating types are released. These infect the copepod and produce a thallus that eventually gives rise to gametangia. The gametangia release motile gametes that fuse either inside or outside the host. The resulting diploid zygote can only infect a mosquito larva. (Adapted from Whisler et al., 1975).

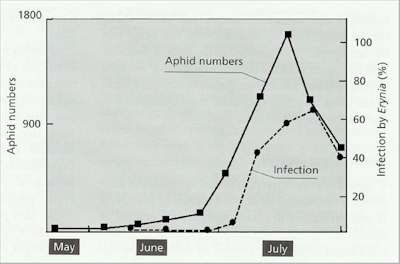

Fig. 15.6. Numbers of aphids (Aphis fabae) in a broad bean crop during a growing season in Britain (solid line) and percentage infection by the pathogenic fungus Pandora neoaphidis (broken line). Based on data in Wilding & Perry, 1980).

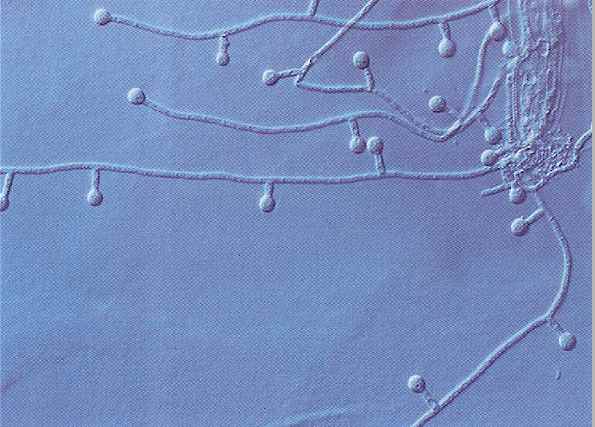

Fig. 15.8a. Adhesive network of the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Image reproduced by courtesy of Professor Bruce Jaffee, University of California, Davis [© B. Jaffee]

Fig. 15.8b. Adhesive knobs of the nematode-trapping fungus Monacrosporium ellipsosporum on hyphae growing from a parasitised nematode.Image reproduced by courtesy of Professor Bruce Jaffee, University of California, Davis. [© B. Jaffee]

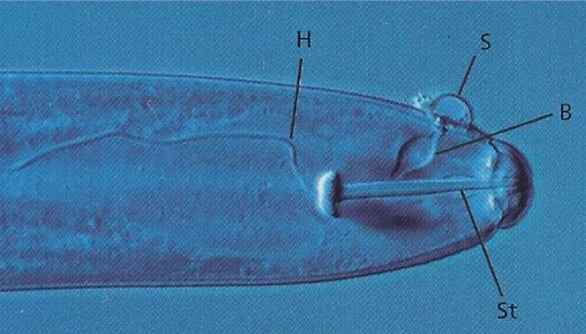

Fig. 15.9. Hirsutella rhossilliensis, an endoparasitic fungus on a nematode host. Infeection occurred from a spore (S) that adhered near the nematode's mouth and then germinated and penetrated the cuticle to produce a bulb (B). A thin infection hypha (H) has started to colonise the host. [The nematodes's piercing stylet (S) is shown; this is used for feeding.] Image reproduced by courtesy of Professor Bruce Jaffee, University of California, Davis. [© B. Jaffee]

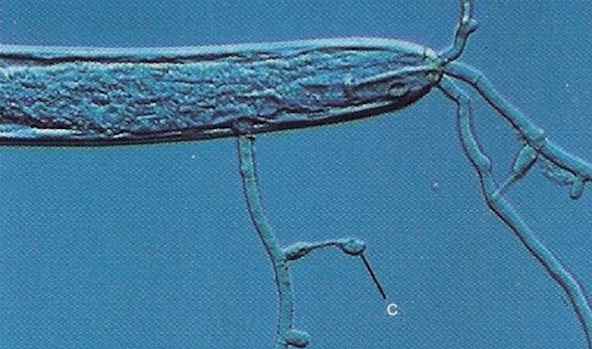

Fig. 15.10. Hirsutella rhossilliensis at a later stage when the body contents have been completely colonised by the fungus. Hyphae have grown out from the dead nematode and produced adhesive conidia (C). Image reproduced by courtesy of Professor Bruce Jaffee, University of California, Davis. [© B. Jaffee]

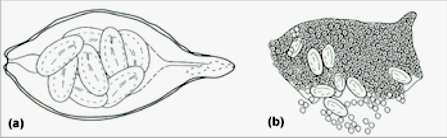

Fig. 15.11. A female cereal cyst nematode, Heterodera avenae, and the cyst-parasitic fungus, Nematophthora gynophila (Oomycota). (a) Mature healthy nematode containing embryonated eggs. The body wall of the female will subsequently develop a leathery cuticle and become a cyst that persists in soil. (b) A ruptured cyst filled with oospores of N. gynophila. Most of the eggs are not infected, but the absence of a cyst wall enables egg parasites such as Verticillium chlamydosporium to infect and destroy many of the eggs. (Drawn from photographs in Kerry & Crump, 1980). |

||||||||||||